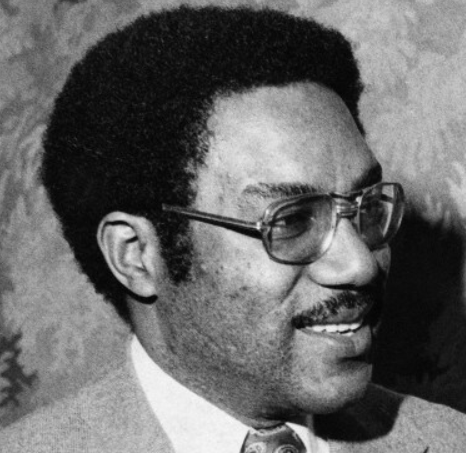

Last year, I wrote about a family trip to Montgomery County, NC, and I promised to follow up on a few “mysteries” of the little town Mt. Gilead. Better late than never, right? Today, I’m writing about one of the faces painted on a mural in Mt. Gilead: Julius L. Chambers.

Obviously, Mr. Chambers was an important person in the town of Mount Gilead — but why? Well, it turns out that he made a huge impact on the Civil Rights Movement in North Carolina (and beyond). He was born in Mt. Gilead in 1936, the third child of William and Mathilda Braton Chambers (they would have four children, all of whom attended college and graduate school). His father owned an auto-repair/general store in Mount Gilead.

Education was extremely important to the Chambers family, and Julius’ older siblings attended the Laurinburg Institute, a private Black preparatory school (its history is another story in itself!). However, Julius didn’t have this advantage because of an incident that happened around 1948, when a white customer refused to pay his father for service.

“But one April day, fighting back tears, William Chambers told his son that the $2,000 he’d saved to send him to school was gone, thanks to a white customer whose 18-wheeler Chambers had maintained and repaired for months, buying parts out of his own pocket. That morning, the man had refused to pay the bill and jeered as he drove off with the rig. William Chambers spent the afternoon going door to door, asking for help from the few white lawyers in town. They all turned him away. That was the day Julius Chambers vowed to study law.” (Article by Dannye Romine Powell and David Perlmutt, The Charlotte Observer)

So, Chambers attended the public Black high school in nearby Troy — as well as having no library, “students had to kill and cut up hogs on the principal’s farm” (The Charlotte Observer). Julius joined a Book of the Month club to make up for gaps in the school’s curriculum, but still wasn’t as prepared for college as his older siblings, who’d attended the much better Laurinburg Institute. (As a side note, that’s not to say that Black teachers were lacking. Malcolm Gladwell has a great podcast, Revisionist History, where he talks in great detail about this. Check it out!)

Despite the odds, Chambers powered forward and earned admission to “North Carolina College” in Durham (now N.C. Central University), where he became student body president and graduated “summa cum laude.” He went on to earn a Master of Arts in European history at the University of Michigan, followed by a law degree at the UNC Chapel hill, newly integrated only eight years earlier. At UNC, he became the first Black editor-in-chief of the North Carolina Law Review and ranked first in his class of 100 upon graduating.

“Although he graduated first in his law school class of 1962, he could not attend the school’s celebratory banquet because of its location at a segregated country club.” (blackpast.org)

But Chambers didn’t let this incident derail him. In 1964, he worked toward his second Master’s degree from Columbia University Law School and began interning for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF). Future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall himself selected Chambers for the position, which was the start of a long and historic career in civil rights.

After finishing up at Columbia, Chambers moved back to North Carolina and opened a civil rights law practice in Charlotte. The first lawyer he recruited was white — Adam Stein from Washington, D.C., — marking the first time a Black and white lawyer had joined forces in the South (not just in NC). With the recruitment of more lawyers, the firm became “Chambers, Stein, Ferguson, & Atkins” and took on hundreds of civil rights cases, challenging everything from discrimination in public hospitals to saving the jobs of Black teachers unfairly dismissed during integration. One of his most famous cases was Swann V. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education:

“Together with lawyers of the LDF, they helped shape civil rights law by winning benchmark United States Supreme Court rulings such as the famous decision of Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education (1971), which led to federally mandated busing, helping integrate public schools across the country.” (https://www.thehistorymakers.org/biography/julius-chambers-39)

In retaliation for shaking up a system that had always favored them, disgruntled White people used violence to try to intimidate Chambers. It didn’t work. In 1965, after Chambers sued to integrate the “Shrine Bowl,” an annual all-star football game held in Charlotte, his home and the homes of three other Charlotte civil rights leaders were blown up. Chambers and his wife, Vivian Giles Chambers, had been in bed when the sticks of dynamite were thrown into their home.

“I threw up next to the house. I was angry,” he told the Observer recently. “I didn’t know who did it. I didn’t know why they would do it. I had my ideas. We knew getting with the Shrine Bowl was going to cause a lot of problems. And it did.” Chambers told the Observer he felt the Shrine Bowl lawsuit was one of his most important civil rights cases. “We were able to reach a lot of parents, teachers, principals, who played very important roles in black and white communities,” he said. (Charlotte Observer)

Chambers’ office and his car were also firebombed. But he kept on.

“The animosity toward him and his positions was just heavy and real. You could feel it,” said C.D. Spangler, former UNC president, who came on the school board in 1972 after Chambers had sued that board and won. “But he never let that change him personally.… He didn’t hate the people who hated him.” (Charlotte Observer)

Chambers’ is described as a “quiet” and “softspoken” person, which makes me think of the saying, “Still waters run deep.” His opponents underestimated him, it’s clear, and he used this to his advantage in the courtroom.

“A lot of people were surprised to see Chambers in court,” said his partner James Ferguson. “Some people expected him to be bombastic and always on the attack. Chambers never raised his voice. He was always very low key and very calm, and because of this approach, he disarmed the witness.” John Gresham, a former law partner, said Chambers had a habit of playing with string or a rubber band, often making a cat’s cradle, while interrogating a witness – lulling the witness into a false sense of security. Another tactic, Gresham said, was to start out asking innocuous questions that appeared to be aimed at finding out very simple things about the company’s policies. “You could see the witness relaxing and thinking, ‘This guy doesn’t even know how we operate.’ Then Chambers would very carefully draw a circle around what he wanted to know, and as soon as he had the loop closed, he would bore in, and you could see the witness thinking, ‘Oh, my God!’” (Charlotte Observer)

The second half of Chambers’s life was no less active — from serving the NAACP-LDF as their third director-counsel and successfully defending affirmative action and other civil rights laws to leading North Carolina Central University as the chancellor. It is impossible to capture all of Chambers’ accomplishments and struggles in one blog post, but at least we have a small understanding now why Mt. Gilead is so proud to call Julius Chambers one of their own. Mr. Chambers died in 2013 and the age of 76 in Charlotte, NC, survived by his two children Derrick and Judy, and three grandchildren. Among many honors, a statue, high school, and highway now bear his name.

Sources/For more information:

Reading, Writing, and Race: The Desegregation of the Charlotte Schools, by Davison M. Douglas

https://www.charlotteobserver.com/news/local/article116679528.html

https://www.thestate.com/news/local/civil-rights/article14438921.html

https://web.archive.org/web/20040918083340/http://www.unctv.org/biocon/jchambers/timeline.html

Leave a comment